Spotlight: Chris Vermont

“Sorry I won’t be able to supervise your Long Vac Term. Have left for Italy to fight the elections for the Communist Party. See below reading list”.

Such was the scribbled message from Paul Ginsborg, my new SPS Director of Studies, on his door in Free School Lane circa June 1980. At the time the Partito Comunista Italiano regularly polled in excess of 30% of the popular vote and led various regional assemblies. So having a fully paid up member of the Communist Party as my DoS did not seem as radical then as it might now. Moreover, this was politics in action, not some dry academician.

Back then SPS could only be studied after completing Pt 1 in a more “respectable” subject (in my case Geography) and the offer of a few extra weeks during the summer Vac seemed like a low stress way to make the transition (combined with Magdalene’s offer of a double set with drawing room overlooking the Cam). A productive 5 weeks followed, albeit mostly working out of the Mill as a chaufferpunt, paying off my first year overdraft.

In the 70’s and 80’s SPS had something of an alternative reputation. As much emphasis was placed on studying the Soviet Union as the USA. It seemed possible to select the most interesting subjects, including from other faculties, often taught by supervisors (usually Kings) who were intractably opposed to Western capitalism. The paper on Revolution (effectively 1789 France to 1978 Iran) was one of the high points, along with the fact the SPS had the only library in Cambridge where you could smoke (restricted to the upstairs section and preferably French tobacco…). The only disappointment was being told I couldn’t sign up for the Womens’ Paper as it was not open to men.

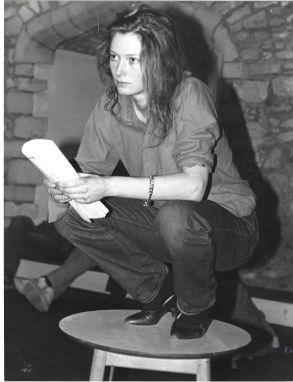

In terms of work pressure, the prevailing atmosphere was laissez-faire, except for much reviled Statistics, which was one of the compulsory papers. Exams at the end of the first year were voluntary and by judicious choice of subjects, it was possible to avoid almost entirely any morning lectures. The pace might not have been demanding compared with other Cambridge courses but the intellectual stimulus was immense. I also developed various side lines, including promoting plays at the ADC and the Marlowe Society, culminating in the 1982 production of the Alchemist at the Arts Theatre, starring fellow SPS student Tilda Swinton together with Simon Russell Beale.

From Cambridge, I stumbled into a job in South Asia and Middle East finance at the late lamented Grindlays Bank, which included postings to Calcutta and Delhi. The First Gulf War of 1990 offered a fascinating glimpse into the interplay of politics and economics. Most economists point to chronic fiscal and trade deficits as the reason for India’s financial crisis in 1990. But the immediate cause was an almost tripling of crude oil prices following Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait.

Foreign exchange reserves plummeted below one month’s import cover and even though oil prices fell back rapidly in early 1991 with Middle East military intervention by the US led coalition, India’s crisis persisted. An arcane 1989 change in its double taxation treaty with Japan removed a tax subsidy to Japanese banks lending to India. India had come to rely on Japanese banks for almost 70% of its private sector bank borrowings and overnight this source of liquidity disappeared. In desperation, the Indian government shipped 47 tonnes of gold reserves to the Bank of England as security for a $400m loan. During 1991, I busied myself arranging emergency short term funding for Indian Oil Corporation to help them buy Oil from BP and others - India’s crisis showed no sign of abating. A call came from the Bank of England in late 1991 to ask if Grindlays could take over the loan if the Bank continued to hold the gold as collateral, as it was not in their charter to lend to other countries. I was despatched to Delhi to negotiate terms with then Finance Secretary, Montek Singh Ahluwalia (PPE, Oxford). Ahluwalia and Finance Minister (later Prime Minister) Manmohan Singh (Economics, Cambridge) were fighting to push the famous 1991 economic reforms through an obstructive parliament.

“I am so sorry you have had a wasted journey to Delhi” murmured the soft spoken Ahluwalia “…we have decided to repay the loan. Our economic situation is improving and we need to extend the appearance of crisis for another 3 months to get the final reforms through parliament. If we repay the loan our published reserves will rise less quickly and we can keep our foot on the accelerator of reform”.

Emerging market banking was quite fun but I took the opportunity to bail out in 2006 when asked to set up a new financial guarantee company called GuarantCo, aimed at recycling domestic savings into productive infrastructure in Africa and Asia. DFID and their counterparts in the Netherlands, Sweden and Switzerland were growing frustrated at the unimaginative way the World Bank Group and others threw dollars at countries, creating high indebtedness.

Developing countries needed infrastructure but these assets did not generate dollars as their citizens paid for services in local currency. In essence, the debate was between expediency and sustainability. Offshore finance might get a power project built quickly so school children could do their homework at night but long term loans need to be paid back by exchanging often fast depreciating local currency. Furthermore, development finance institutions frequently crowd out commercial lenders, especially local ones, inhibiting local financial ecosystems developing and exacerbating aid dependency. Local currency finance needs lengthy and time consuming capacity building in often nascent and fragile financial markets but is ultimately more sustainable.

The natural evolution from London based GuarantCo has been to set up individual guarantee companies with local management and capital. I helped set up the first, InfraCredit Nigeria - which commenced operations last year - and part of a team with plans for similar initiatives in Kenya, Pakistan, Egypt and beyond. Meanwhile, the use of guarantees to mobilise finance has gained considerable traction since GuarantCo was set up. The latest example, at which I have the somewhat pompous title of Senior Guarantee Expert, is the European Fund for Sustainable Development, a Eur 4bn initiative to belatedly address the causes of economic migration into the EU. EFSD seeks to accelerate investment in infrastructure and job creation in Africa and EU neighbouring countries. While the Commission staff in Brussels would dearly like to take the sustainable route, sadly, at the time of writing, it looks like the politicians will force expediency, at least for the first phase.

Did the lack of supervision during that Long Vac Term in 1980 have any lasting effect? In a way it did. It was an early lesson that academic appraisal and practical action should go hand in hand. Both are required if we are to make a better world.

Chris Vermont is the Senior Expert to the EU on a financial guarantee programme to address the causes of economic migration.